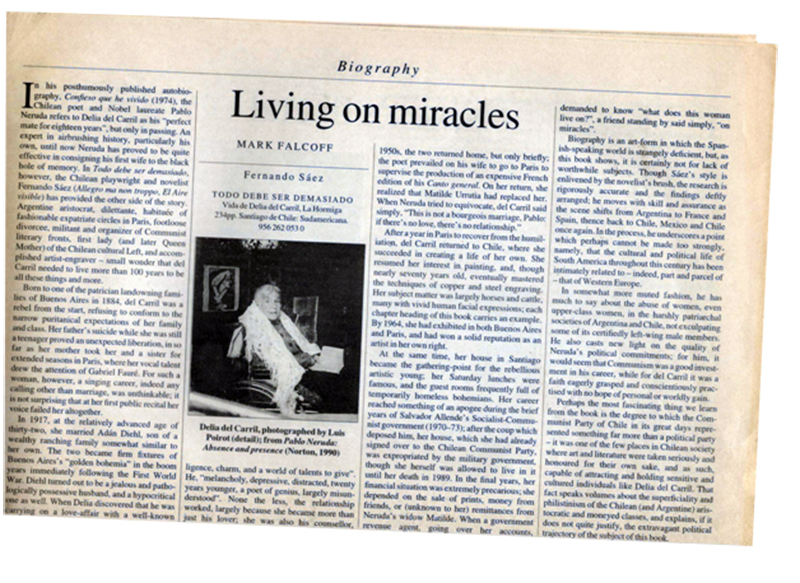

Reseña del libro «Todo debe ser demasiado, biografía de Delia del Carril» de Fernando Sáez que saldrá en mayo de 2021 con la editorial Fiction Advocate, traducido por Jessica Sequeira.

Living on miracles

Mark Falcoff

in Times Literary Supplement

review of Todo debe ser demasiado

Vida de Delia del Carril, La Hormiga

234pp, Santiago de Chile: Sudamericana

1998

956 262 053 0

In his posthumously published autobiography, Confieso que he vivido (1974), the Chilean poet and Nobel laureate Pablo Neruda refers to Delia del Carril as his “perfect mate for eighteen years”, but only in passing. An expert in airbrushing history, particularly his own, until now Neruda has proved to be quite effective in consigning his first wife to the black hole of memory. In Todo debe ser demasiado, however, the Chilean playwright and novelist Fernando Sáez (Allegro ma non troppo, El aire visible) has provided the other side of the story. Argentine aristocrat, dilettante, habituée of fashionable expatriate circles in Paris, footloose divorcee, militant and organizer of Communist literary fronts, first lady (and later Queen Mother) of the Chilean cultural Left, and accomplished artist-engraver — small wonder that del Carril needed to live more than 100 years to be all these things and more.

Born to one of the patrician landowning families of Buenos Aires in 1884, del Carril was a rebel from the start, refusing to conform to the narrow puritanical expectations of her family and class. Her father’s suicide while she was still a teenager proved an unexpected liberation, in so far as her mother took her and a sister for extended seasons in Paris, where her vocal talent drew the attention of Gabriel Fauré. For such a woman, however, a singing career, indeed any calling other than marriage, was unthinkable; it is not surprising that at her first public recital her voice failed her altogether.

In 1917, at the relatively advanced age of thirty-two, she married Adán Diehl, son of a wealthy ranching family somewhat similar to her own. The two became firm fixtures of Buenos Aires’s “golden bohemia” in the boom years immediately following the First World War. Diehl turned out to be a jealous and pathologically possessive husband, and a hypocritical one as well. When Delia discovered that he was carrying on a love-affair with a well-known Spanish ballerina in 1921, she simply packed her bags and decamped to Paris, without even bothering to arrange a financial settlement. When she returned to Buenos Aires, she was able to set up her own household, thanks to regular remittances from her father’s estate.

In 1929, del Carril returned to Paris, where, as an attractive Argentine divorcee of independent means, she found immediate entrée into avant-garde cultural circles. She mixed with luminaries like Marinetti and Saint-Exupéry, but also with Picasso, Le Corbusier, Eluard and Louis Aragon. Shortly thereafter, her family fortunes experienced a sharp decline as a result of the Great Depression, and del Carril underwent a serious conversion to Communism. In this, Aragon seems to have played an important role, not only steering her to the proper literature but sponsoring her entry into the French Communist Party.

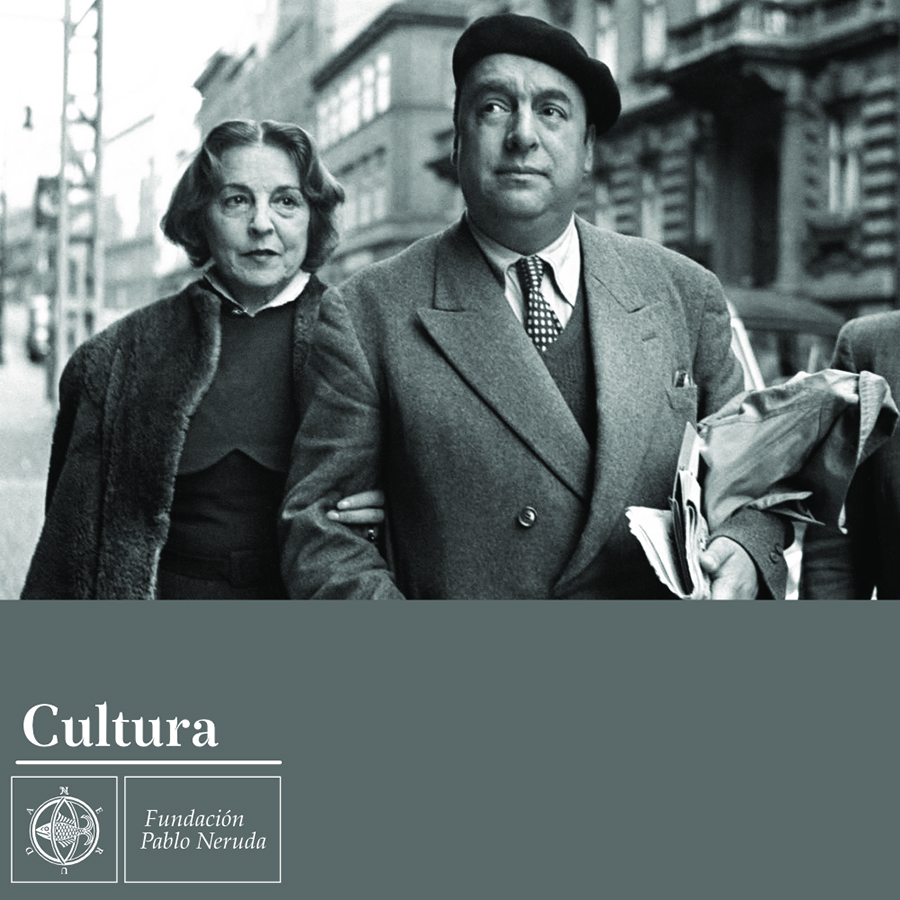

In 1934, she moved to Madrid, where the Second Republic was becoming the focus of international left-wing sympathy. Through the good offices of the Argentine poet Rafael Alberti, she was immediately introduced to the city’s dazzling literary and artistic establishment, though it was through an elegant Chilean diplomat, Carlos Morla, that she was to make her most important contact. At one of his soirées, she was introduced to Pablo Neruda, who was then Chilean consul in Barcelona, but was better known as one of the great poets of the Spanish language. Neruda arrived in the company of his friend Federico García Lorca, jostling past the likes of Vicente Aleixandre, Luis Cernuda, Jorge Guillén, Miguel Hernández and Luis Rosales. The fascination was mutual, and within weeks the two had set up housekeeping together.

“Could there be two persons more different?”, asks Sáez. She, a woman “with an almost glamorous past, enriched by beauty, originality, intelligence, charm, and a world of talents to give”. He, “melancholy, depressive, distracted, twenty years younger, a poet of genius, largely misunderstood”. None the less, the relationship worked, largely because she became more than just his lover; she was also his counsellor, mother-confessor, editor, secretary and factotum. She was also the more serious of the two when it came to left-wing politics. Although Neruda’s Communist associations eventually forced him out of the Chilean foreign service, it was del Carril who was the more dependable comrade. Her friends in the Spanish party used to refer to her as “Molotov’s eye”, although Neruda himself, perhaps in tribute to her capacity ofr work, liked to call her “the ant” (“la hormiga”).

During the run-up to the Spanish Civil War, Neruda and del Carril were important personalities in the world of Popular Front intellectuals. In the final days of the Republic, they moved to France, before returning to Chile. They remained there for a brief period before taking ship to Mexico, where Neruda held his last diplomatic assignment. Going back to Chile after the Second World War, del Carril accompanied her husband on the hustings as a candidate for the Senate on the Communist Party ticket. Shortly after his election, an anti-Communist crusade unleashed without warning by President Gabriel González Videla forced both of them into hiding, until party agents were able to spirit them out of the country and thence to Capri. (The account here corrects somewhat the scandalously fictitious version of their residence on the island presented in the film Il Postino.)

Proscribed in Chile, Neruda became an international celebrity, a status he would enjoy until his death twenty years later. He and del Carril made two pilgrimages to the Soviet Union, where they were received by Stalin himself, who gave Delia a splendid fur coat with red silk lapels. Other trips followed to Romania, Hungary, even the People’s Republic of Mongolia. Eventually the two left Capri for Mexico, where a young Chilean woman, Matilde Urrutia, attached herself to their household. When the Chilean Government lifted the ban on Communists in the mid-1950s, the two returned home, but only briefly; the poet prevailed on his wife to go to Paris to supervise the production of an expensive French edition of his Canto general. On her return, she realized that Matilde Urrutia had replaced her. When Neruda tried to equivocate, del Carril said simply, “This is not a bourgeois marriage, Pablo: if there’s no love, there’s no relationship.”

After a year in Paris to recover from the humiliation, del Carril returned to Chile, where she succeeded in creating a life of her own. She resumed her interest in painting, and, though nearly seventy years old, eventually mastered the techniques of copper and steel engraving. Her subject matter was largely horses and cattle, many with vivid human facial expressions; each chapter heading of the book carries an example. By 1964, she had exhibited in both Buenos Aires and Paris, and had won a solid reputation as an artist in her own right.

At the same time, her house in Santiago became the gathering-point for the rebellious artistic young; her Saturday lunches were famous, and the guest rooms frequently full of temporarily homeless bohemians. Her career reached something of an apogee during the brief years of Salvador Allende’s Socialist-Communist government (1970-73); after the coup which deposed him, her house, which she had already signed over to the Chilean Communist Party, was expropriated by the military government, though she herself was allowed to live in it until her death in 1989. In the final years, her financial situation was extremely precarious; she depended on the sale of prints, money from friends, or (unknown to her) remittances from Neruda’s widow Matilde. When a government revenue agent, going over her accounts, demanded to know “what does this woman live on?”, a friend standing by said simply, “on miracles”.

Biography is an art-form in which the Spanish-speaking world is strangely deficient, but, as this book shows, it is certainly not for lack of worthwhile subjects. Though Sáez’s style is enlivened by the novelist’s brush, the research is rigorously accurate and the findings deftly arranged; he moves with skill and assurance as the scene shifts from Argentina to France and Spain, thence back to Chile, Mexico and Chile once again. In the process, he underscores a point which perhaps cannot be made too strongly, namely, that the cultural and political life of South America throughout this century has been intimately related to — indeed, part and parcel of — that of Western Europe.

In somewhat more muted fashion, he has much to say about the abuse of women, even upper-class women, in the harshly patriarchal societies of Argentina and Chile, not exculpating some of its certifiedly left-wing male members. He also casts new light on the quality of Neruda’s political commitments; for him, it would seem that Communism was a good investment in his career, while for del Carril it was a faith eagerly grasped and conscientiously practised with no hope of personal or worldly gain.

Perhaps the most fascinating thing we learn from the book is the degree to which the Communist Party of Chile in its great days represented something far more than a political party — it was one of the few place in Chilean society where art and literature were taken seriously and honoured for their own sake, and as such, capable of attracting and holding sensitive and cultured individuals like Delia del Carril. That fact speaks volumes about the superficiality and philistinism of the Chilean (and Argentine) aristocratic and moneyed classes, and explains, if it does not quite justify, the extravagant political trajectory of the subject of this book.00