by Jessica Sequeira

Zulfikar Ghose is a novelist, poet and critic. He has written fiction (such as The Murder of Aziz Khan, The Incredible Brazilian trilogy, Hulme’s Investigations Into the Bogart Script and A New History of Torments), non-fiction (such as Confessions of a Native-Alien,The Fiction of Reality and In the Ring of Light) and poetry (such as The Loss of India and Jets from Orange). Born in 1935 in Sialkot, India (now Pakistan), Ghose emigrated to England in 1952, where he graduated from Keele University with a BA in English and Philosophy, was a cricket correspondent for The Observer, and wrote journalism for the Times Literary Supplement, The Spectator and Western Daily Press. In 1960, he met the novelist and poet B. S. Johnson, with whom he became close friends, and in the same year he joined The Group—a collection of poets who met at Edward Lucie-Smith’s house in Chelsea to discuss their work. These meetings were attended by, among others, George MacBeth and Philip Hobsbaum, and occasionally Ted Hughes. In 1969, Ghose emigrated to the United States to teach creative writing at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is now Professor Emeritus. He lives with his wife Helena de la Fontaine, an artist from Brazil whom he married in London.

Ghose writes of “the mind’s coition with beauty”, and quotes Fernando Pessoa on “the natural splendor of interior life, with its natural Indies and its unknown lands”. Yet he is also concerned with bringing archetypes and associations into the “continuous action” of image-driven plot, forging situations of comic absurdity and adventure in the Amazon rainforest, the textile mills of Pakistan and the Texan wild west. Place comes to seem the externalized labyrinth of the human mind in Ghose’s page-turners, chock full of humor and lyricism.

It’s an age-old question for a writer: how to express the complexities of inner life, along with the spryness and sensuality of the outer world? Ghose is one of my favorite living writers precisely because I think he does this remarkably well. Devoted to the adventure of consciousness, as well as to the texture of nature and cityscapes, he patterns ideas into plot. The result is something complex and satisfying at the level of both phrase and overall structure.

In his essayistic work, Ghose is a reader first, and wears both his admiration and his thoughtful critique of other writers on his sleeve. In a defiant voice, he lays down gauntlets, such as: “the genuine avant-garde is to be recognized by its fidelity to precision of expression”. A consummate stylist, he quotes Roberto Calasso regarding—and himself practices—the desired “vibration or luminescence of the sentence (…) sufficient unto itself”. Again and again he circles back to the idea of language giving birth to new forms of understanding reality.

Along with all this, Ghose is very charming over email, which is where this conversation took place.

- You were born in Sialkot, India (now Pakistan), then moved to Bombay, and then to London where you began to write poetry and meet figures such as Ted Hughes, Silvia Plath and B.S. Johnson (with whom you wrote the book Statement Against Corpses). Could you talk a little about this move from Bombay to London, and how your writing career in the UK and the book with Johnson came to be?

I had grown up in Bombay which was a beautiful cosmopolitan city in the 1940s, unlike the present slum infested mess called Mumbai. The British had developed Bombay as an important outpost in their Empire. Going to Don Bosco High School, a Catholic school run by Italian priests where the teaching was in English, I was attracted to Byron’s poetry at the age of 14 and began to write poems in imitation of his. There was a cinema very near the school and sometimes when the film poster showed some eye-catching image, I fell for the temptation to slip out of class and go see the film, often a Western with a lot of six-shooter gun action. One day, the curious film was set in a castle in Denmark. It was Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet, and that is when I discovered Shakespeare. I soon became drawn to English literature, especially the way language could shape a variety of forms, and began to understand that it was not its content, its idea, that gave a poem its quality but the imagistic compression of its language that released an unexpected thought in the mind, like a faintly heard music.

In 1952, my family emigrated to England and settled in London where I finished my schooling at a grammar school and then went on to Keele University to read English and Philosophy for my B. A. I was fortunate to have a Shakespeare scholar as headmaster at the grammar school and two highly learned English teachers who, appreciating my interest in literature, even leant me their own books to read. At the university, I spent more time writing my own poems and prose and reading modern literature than attending to the academic course work, only doing enough of it just to pass, but by the time I graduated and returned to London I had begun to publish my poems and essays in national magazines, enough to be noticed as a promising new writer.

Various accidents— such as meeting writers at poetry readings or joining groups who met in cafés and pubs—led to my becoming acquainted with other writers, especially poets, who were just becoming established. Of these, B. S. Johnson became my closest friend and the two us met frequently in pubs and talked for hours about new writing. He was drawn to James Joyce and Robert Graves, I to William Faulkner and T. S. Eliot. One day, we happened to be talking of the short story form and it occurred to us that at that time, around 1963, no English writer was producing formally interesting work and, with the usual conceit of young writers that they were the genius of their age, concluded that it was up to us to rectify that situation. Next thing, within a few months we each wrote a group of formally experimental stories, and since Johnson had written a prefatory statement and I had a story called ‘The Corpses’, we titled the book Statement Against Corpses.

- Later on you moved to Texas with your Brazilian wife and began to write novels set in South America. While your early work seems concerned with probing and questioning the East-West dichotomy, in London and then Texas you begin to develop a prose that moves beyond national boundaries. Would you please talk a little about this transition in your thought?

I had begun to write The Incredible Brazilian, my first novel set in South America, when still living in London with my wife Helena. In 1966-67, we had visited her homeland, flying to Rio de Janeiro, staying there and later in São Paulo with her extended family, and going on a fortnight’s adventurous incursion into the interior. Brasília was being built then and the road from Rio to there was little more than a track in the dust for much of the way. From Brasília we ventured further west into the primitive jungle interior. Thus, I had seen a good portion of the country in that three-month visit. On returning to London, I happened to be browsing in a bookshop some months later and chanced on a book titled The Masters and the Slaves by Gilberto Freyre.

I had never heard of Gilberto Freyre, but glancing at some of his text I became curious and purchased the book. It was, I discovered, one of the great works of twentieth-century anthropology. Reading it, I began to imagine the early Brazilian society that is the subject of Freyre’s study. The conception in my imagination became vastly elaborate as I put down the images invading my brain. I’d picked up another book which was a documentary history of Brazil, and the country’s history playing out in one part of my brain and images of its social development flooding the rest, before I knew it I was working on a novel.

In the meanwhile, it was now 1968. I had a full-time job as a school teacher in London, and also did some freelance journalism. I had begun to receive a lot of attention after the publication of two books of poems and my second novel, The Murder of Aziz Khan, and was invited to New York to take part in the Lincoln Center Poetry Festival at the 92nd Street Y. My performance there was well received. There was to be another poetry festival a few days later at SUNY in Stony Brook on Long Island; this was billed as the Stony Brook World Poetry Conference to which 108 poets had been invited, including such international stars as Zbigniew Herbert, Nicanor Parra and Ingeborg Bachmann; at the last minute Bachmann withdrew and I was invited to replace her; many of the major American poets were also at the festival and my reading there led to my being invited to yet another international festival to take place at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. in 1970. International poetry festivals were very popular in the 1960s. Early in the decade there was one in London, held in the Royal Festival Hall, where the greatest names among the world’s living poets performed before packed audiences. One of the poets who had me mesmerized as he stood alone on the stage in a blue suit looking much like a banker or a diplomat as he recited his poems was Pablo Neruda.

On my returning to London from New York in the summer of 1968, another series of accidents found me corresponding with the University of Texas that resulted in my being invited to go there to lecture on English literature. So, my wife and I went there in September 1969 for a provisional appointment that became permanent, and 51 years later we still live there. All that travelling in 1968 and then the move to Texas distracted me from working on the novel I’d begun based on Brazil’s early history. As luck would have it, the University of Texas had one of the best Latin American libraries in the world, and I was able to look up more highly detailed Brazilian history. A year later I had written enough of a first draft of my novel to send it to my publishers, Macmillan in London. They were so thrilled by what they saw that they sent me a cable with a generous offer. Seeing how eager they were to accept it, this is when I decided to make it into a trilogy and get Macmillan to triple the money. And so, the first volume of The Incredible Brazilian came out in 1972 in London.

Now, it happened that One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Márquez had been published five years earlier and already there had been a good deal of talk about magical realism and the Latin American boom; therefore, when my novel, which contains many magical moments that are yet realistic in their details, was published, some readers assumed I had been influenced by the Márquez novel. However, the truth is that I had not even heard of Márquez and nor had I read much fiction. Though by now I had written four novels and some short stories, most of my literary energy, both reading and writing, had been devoted to poetry. Also, the main course I taught when I began work as a professor at the University of Texas was on modern British and American poetry. I was not sufficiently prepared to work at the professorial level and therefore had to give most of my reading time to poetry, especially to several American poets, such as Hart Crane and Wallace Stevens, whom I had not yet read with the necessary care in order to be prepared to lecture on them. As for the novel, I had not read any of the major works, not even Quixote or the Arabian Nights or the late great works of Charles Dickens. And so, the forms taken by the fictions I wrote were generated by some instinct in my brain without any preconceived notion of what I was doing. The only narrative plan I had was to stop a day’s writing at an intriguing and nearly unbelievable situation in the narrative and hope to come up the next day with a new development that would make it believable.

- Your novels are intricately patterned, with narratives running in parallel, and poetry at the level of both sentence and structure. What is your process of composition in creating such complex works?

My concluding remark in the previous answer addresses this question. I spent four years after the publication of the first volume of The Incredible Brazilian trilogy working on the next two volumes as well as the novel titled Hulme’s Investigations Into the Bogart Script which began by itself but once begun required me to read many historical texts. During these years I also read widely in literature and criticism, finally catching up with Márquez and magical realism only to find there was nothing exceptionally new about it that was not already in Rabelais, Cervantes and the Arabian Nights, which I also read for the first time during these years.

Perhaps the philosophy I’d read as an undergraduate was directing my brain but during my intensive reading in the 1970s and 80s I’d come to believe that human perception was continually engaged in an interpretation of reality, reducing it to a projection of signs and symbols which we called language whether they were a series of words on a page or a formula in physics or paint thrown at a canvas. Language and silence. Aristotle to Wittgenstein. Humans craved for meaning, always looking for the language that would convey some ultimate truth. Rabelais had already worked it out, creating a character in his novel who uttered a series of nonsensical sounds that were heard as an unknown language which might well reveal that ultimate truth. Some of these ideas led me to write two of my books of criticism, Hamlet, Prufrock and Language, and The Fiction of Reality.

- You have written of the novelist as an anthropologist, tracing out symbols and metaphors, and studying tribes and societies widely defined. At the same time, your work seems to present ideas of archetypal myth. How do you balance the specific and the universal?

One of the books that made a great impression on me when I was an undergraduate was Jung’s Symbols of Transformation. Reading more of his work, his analysis of archetypes and the collective unconscious seemed to describe society perfectly. Later, reading Claude Lévy-Strauss’s Tristes Tropiques confirmed Jung’s idea of the tribal nature of society, and much later, when I wrote my novel The Triple Mirror of the Self, I created a primitive tribal society in its opening section with Jung and Lévy-Strauss possibly in my subconscious. There is a reduction of the self when awareness of one’s being detaches one from the illusion of individuality and what’s left of the self is a shadowy fantom. However, whatever the complexity or the naïveté of the philosophical ideas that charge one’s writing, a writer’s attempt to explain them is no more than a rationalization after the event. The simple truth is that I never know what I am going to write until I have written it; my focus is entirely on the composition of the sentence in front of me, always remembering Nabokov’s injunction, “caress the details”, and that the images that I am trying to project with cinematic clarity are those that are a vital part of that moment’s reality and not chosen because they have symbolic value or have a buried allusion to a myth.

- What is it that attracts you to big landscapes such as the Amazon rainforest, which recurs in your work?

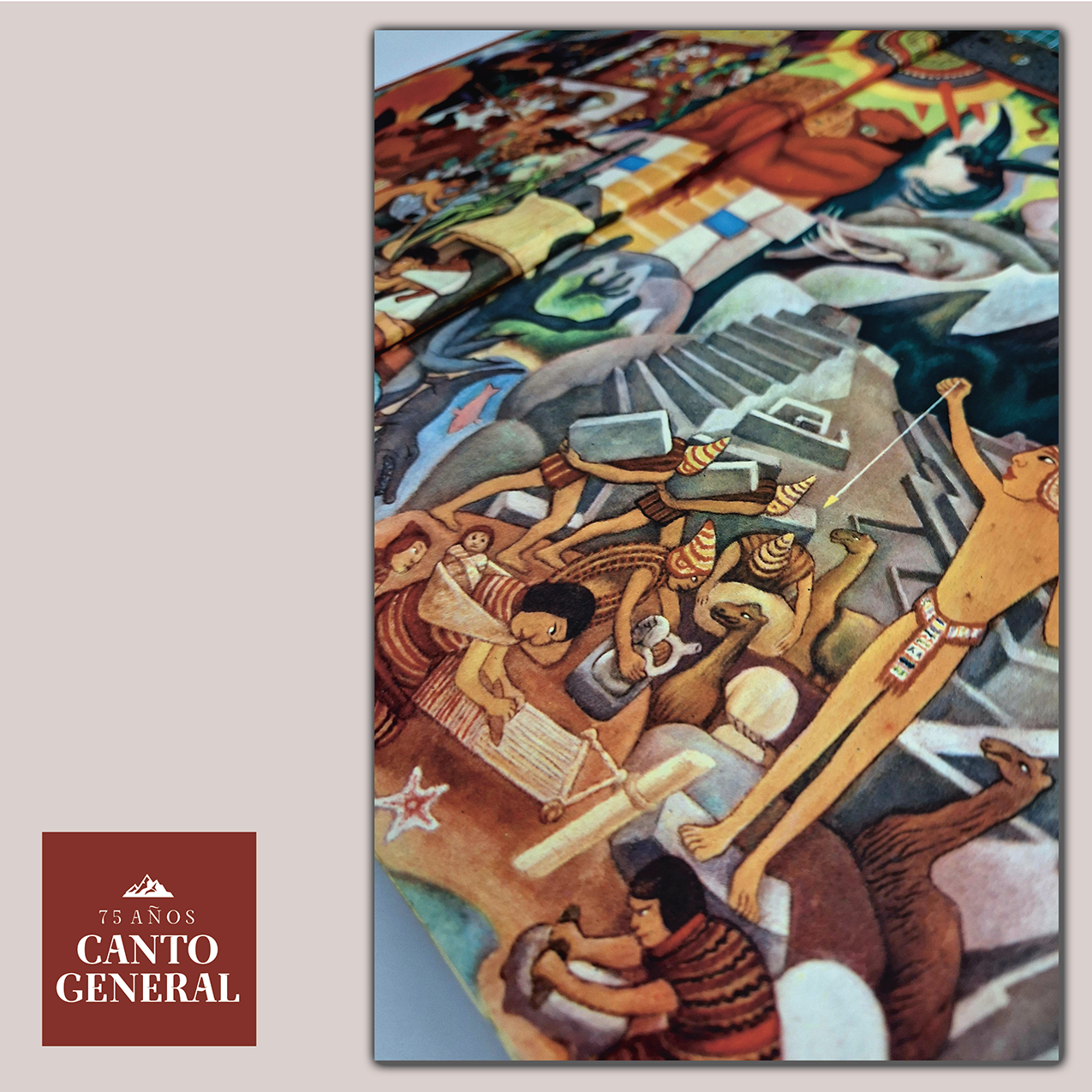

My wife and I spent a week in Belém and Manaus on the Amazon in 1971 which included taking a boat trip into the jungle interior. Although one embarks on such tourism with the psychological anticipation that one is about to experience a sensational vision of a previously unknown reality, what we experienced was the feeling of seeing a world frozen at its original creation. Its imagery was indelibly imprinted on my imagination. When I worked on the second volume of my Brazilian trilogy, The Beautiful Empire, I set its major part in Manaus, and later when I wrote A New History of Torments, there is a section of it in which its main character Jason finds himself in that original world.

Landscapes have always attracted me. My first experience of being bedazzled by the world I looked at was when my family moved from Sialkot to Bombay when I was seven years old and sat by the window in the Punjab Mail, the steam-powered train that cut across India for nearly two thousand kilometers from Lahore to Bombay. From the green fields of the north, the world changed to dusty fields with stunted trees in central India and to a tropical forest as the train wound up the mountain range on the coast and then went hurtling down to the coast, with sudden views of the ocean flashing in the dazzling light. Ten years later, a month before my family emigrated to England, we did the same journey in reverse by car, driving north from Bombay as far as Delhi. The road was little more than a dust track, and much of the landscape was a dusty desolation. I stared at the land of my birth from which I was about to be separated. At some moments it seemed that the landscape I looked at had cut itself from the earth and was beginning to float away into the sky. And in all my future travels I was to stare out at the world as if expecting a restoration of that original world. Flying over Ecuador and looking down at the volcanoes, driving down the length of Brazil to Argentina and across the Andes to Chile, South America rotated the kaleidoscope of the universe in my eyes, now the desolation of the Sertão in the Brazilian northeast, now the blinding emptiness of the Atacama, now hearing the howling monkeys in the Amazonian rainforest, now an eerie silence walking up a path to the towering Osorno before my eyes, looking always, looking, looking for that original lost brightness.

There have been illusory glimpses of it. In The Triple Mirror of the Self it appears in many guises. The Amazonian interior in the first part, the western United States in the second, and India in the third, with the self a petrified fossil in a terminal landscape at the end of that novel.

- You are reflexive about your writing. Your novels often include references to other works and traditions, and in books like In the Ring of Pure Light, The Fiction of Reality and Hamlet, Prufrock and Language you draw connections between traditions such as Sufi mysticism, the French nouveau roman and English modernism. You seem to have a unifying vision, yet are averse to poststructuralist trends in criticism. How would you sum up your own idea of what the novel does?

When The Incredible Brazilian was published, some reviewers referred to its picaresque form. The word “picaresque” had never occurred to me when I wrote it; in fact, I was not sure if I knew what it meant. Structuralism had just then come into academic vogue and I read some of its basic texts. I think it was in André Jolles or in Vladimir Propp that I read about the twenty or thirty stages of a mythic hero’s life. That almost precisely described my hero Gregório’s life. In other words, I did not need a structuralist theorist to outline for me the form I must follow, my brain instinctively knew which turns of the labyrinth I must enter. I was not averse to structuralism or to poststructuralism (whatever that was!). It was just that when I read the structuralists, I found them saying what seemed obvious and self-evident but doing so in a convoluted jargon-filled portentous language. Not only that, they projected themselves as serious scientists by introducing mathematical symbols and diagrams in their writing which, when deciphered, added to zero. But their jargon became the conveniently obscurantist language with which some professors could disguise their banal reading of literature.

As for my idea of what the novel does, I really have no idea. Perhaps it entertains; perhaps it illuminates the self; perhaps it presents a new perception of reality; perhaps it does all these things or nothing at all. One has only to re-read a novel to see it differently from what one saw the first time.

My understanding of Sufi mysticism is rather superficial, and although I reject the beliefs broadcast by the major organized religions, I do think there is an impulse within the human psyche that seeks a mystical merging of the self with a projected other and that the Sufi “I in you, you in me” mantra of becoming one with the deity is commonly experienced in the moment of sexual orgasm. And I speculate, too, that the moment when we are rendered speechless by great art we experience a similar mystical experience, an ecstasy of the soul.

- Absurdist humor plays an important role in your writing. How would you describe the role of comedy in your work?

Again, I have no idea. All that concerns me in my writing is the phrase, the sentence, the paragraph I happen to be working on. It has somehow to be filled with action that is interesting. No doubt, after reading Rabelais and Beckett and seeing Ionesco’s plays, there are influences at work; or those Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton, Jacques Tati films; and not to forget the author of the play in which a woman falls in love with an ass.

- What authors writing today do you admire? What kinds of artistic projects do you find interesting?

There are many fine writers, artists and composers today. I know several of them, some as acquaintances met at festivals or conferences, some as lifelong friends. To name those I admire would be unfair to the ones I forget to name.

- Can you describe a favorite scene from your own books?

No. I don’t read my books and have forgotten what some of them contain. I think in one of my books of criticism I said that my books would be better if I were to write them now, but if I had not written them, I would not want to write them now.

- The author’s note to your novel A New History of Torments references Pablo Neruda. (To quote you: “The title of this novel was suggested by the line, ‘en esta historia de martirios’ in Pablo Neruda’s poem ‘Vienen por las islas (1493)’. The titles of the two parts of this book are the two phrases in the penultimate line in the following quotation from Neruda’s poem ‘Rapa Nui’: Sólo la eternidad en las arenas / conocen las palabras: la luz sellada, el laberinto muerto, / las llaves de la copa sumergida.) What role has Latin American poetry, such as that of Pablo Neruda, played in your understanding of literature and your own writing?

As mentioned earlier, I read intensively after taking up my job at the University of Texas. The University of Texas Press happened to publish a wide range of Latin American writers in its Pan-American Series at that time and the Spanish and Portuguese Department invited eminent writers to come for a semester’s residence. Borges’s first visit to the United States (a year before I came to the university) was to take that post. Next came Octavio Paz. So naturally my curiosity was aroused, and during the years that followed I bought and read a whole range of Iberian and Latin American writers, bi-lingual editions of whose works were published by major university presses and even by mainstream publishers. The three that made the greatest impression on me were Jorge Guillén, Pablo Neruda and César Vallejo. I did not know Spanish but could make sense of it after first reading the translation, enough sense to think, or have the illusion, that I could hear the poetry. What effect this reading had on my writing I do not know. I also read poets from other nations—French, German, Russian, etc.—and then, taking a walk, listening to the birds, then returning home, drinking a gin and tonic, and sitting down to write whatever came out of my brain.