Por Jessica Sequeira

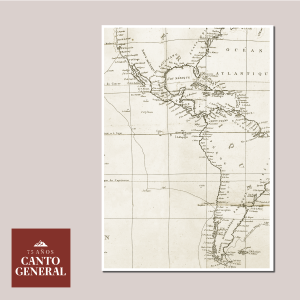

Richard Gwyn (Pontypool, 1956) es un poeta, narrador, ensayista y traductor galés. En 1980, comenzaron diez años de vagabundeo alrededor del Mediterráneo. Su memoir, The Vagabond’s Breakfast, que ganó el Wales Book of the Year, 2012 es, en gran parte, la crónica de esos años de vagabundeo. Fue publicada por LOM en Chile y Pre-Textos en España bajo el título El desayuno del vagabundo. En 2013 apareció la antología de su poesía Abrir una caja (Gog y Magog, Buenos Aires), y luego Ciudades y recuerdos (Trilce, México), ambos traducidos por Jorge Fondebrider. El mismo año se publicó en el Reino Unido The Other Tiger: Recent Poetry from Latin America, la culminación de cinco años de esfuerzo como traductor de poesía latinoamericana. Es autor de cuatro volúmenes de poesía, así como de tres novelas, más recientemente The Blue Tent (2019). Richard Gwyn tiene un alter ego que lleva administra el blog de Ricardo Blanco: www.richardgwyn.me

- ¿Dónde te encuentra la cuarentena? ¿Cuáles son los libros, álbumes y obras de arte más importantes para ti en estos días de aislamiento, si los hay?

No me molesta el lockdown en absoluto. Para un escritor, parece una forma muy natural de pasar los días, aunque extraño mis largas caminatas en las colinas, que disfruto no solo por sí mismos sino también como parte del proceso de compostaje. Solvitur ambulando (se lo resuelve con caminar) es una de las pocas frases en latín que puedo recordar, y parece más cierto con cada año que pasa. Podría terminar simplemente caminando, como ese tipo Walser, o el personaje de Heladas de Thomas Bernhard, que se embarca en interminables ‘expediciones a la jungla de la soledad’. En realidad, durante el encierro, he soñado mucho con caminar, pero no me va a ayudar a perder los kilos que he estado acumulando. Actualmente estoy escribiendo un libro de no ficción sobre mis viajes por Latinoamérica durante 2011 a 2015 mientras compilaba la antología El otro tigre, por lo que mi lectura está dictada en gran medida por eso—o lo estaría, si alguna vez pudiera seguir mis propias reglas. De hecho, la mayoría de los libros que he disfrutado leer durante el encierro han estado relacionados con ensayos que me han pedido que escriba: The Shapeless Unease [Una inquietud sin forma], el estudio de Samantha Harvey sobre el insomnio, y el libro de Marina Benjamin sobre el mismo tema, titulado simplemente Insomnia, un ensayo sobre, adivina qué, insomnio. Me gustó tanto el libro de Harvey que también leí su novela, The Western Wind. Releí Ceguera de Saramago y El amor en los tiempos del cólera de García Márquez, y terminé escribiendo un ensayo sobre la noción muy contemporánea del contagio. Acabo de terminar de leer The Dawn Watch [La vigilia del amanecer] de Maya Jasanoff, una brillante biografía de Joseph Conrad, que examina la forma en que su escritura se adelantó a la globalización. He estado escuchando mucha música abstracta de drones de gente como William Basinski y Sarah Davachi, mientras trabajo en la computadora, un gusto adquirido, lo sé . . . El arte, como el que hay en las galerías, no estuvo tan presente ya que no estoy saliendo, pero hay un recordatorio televisivo constante del nivel de la mierda de todo en el Reino Unido y cómo nuestro gobierno se equivocó terriblemente con el Covid. Cosa deprimente.

- ¿Qué libros fueron gravitantes en tu formación como escritor?

Parece que contesto esto de manera distinta cada vez. Cuando era niño en una casa galesa, mi padre interpretó la grabación de Richard Burton de Bajo el bosque lácteo, así que eso fue una influencia de fondo durante años. Siguiendo con las obras de ficción, Cien años de soledad me persuadió enormemente cuando lo leí por primera vez en mi adolescencia, pero no me gustaría volver a leerlo ahora, ya que sospecho que estaría decepcionado. Me encantaron las Confesiones de un inglés comedor de opio de De Quincey. La montaña mágica fue una revelación, pero también lo fue en su forma V., de Thomas Pynchon, y Les grands chemins, de Jean Giono, que sigue siendo uno de mis novelistas favoritos. Me encantó Ancho mar de los Sargazos de Jean Rhys. El periódico The Independent me pidió una vez que participara en su columna “el libro de mi vida”, y elegí Ficciones de Borges. Probablemente aún lo haría. Vuelvo a los Ensayos de Montaigne una y otra vez.

- Tus novelas, como The Colour of a Dog Running Away [El color de un perro en fuga] y The Vagabond’s Breakfast [El desayuno del vagabundo], y tus libros de poesía, como Stowaway [Polizón], tienden a presentar personajes solitarios que huyen de algo o buscan rehacer su vida. A menudo se encuentran en otros países e idiomas, atrapados en relaciones complicadas y eventos poco probables, luchando entre mantener el control y dejarse ir. ¿Cómo eliges los temas de tus libros y su estilo (novela, poesía, etc.)? ¿O sería un proceso más orgánico?

Todo lo que he escrito se basa, en mayor o menor grado, en mi propia experiencia. Al leer a Borges, me sedujo la idea de que cada instante contiene el potencial para una infinidad de resultados, un motivo recurrente en su obra, o que nuestro universo es solo uno en una multiplicidad de universos posibles, una idea que ocupé en mi novela The Blue Tent [La tienda azul]—o que en lugar de ser los propietarios de nuestra propia conciencia, alguna otra entidad nos está soñando. Me gustan las ideas que presionan los bordes de la comprensión, y siempre he estado insatisfecho con las sabidurías recibidas. La idea de múltiples vidas—y de múltiples mundos—es una que ha estado conmigo desde que tengo memoria. Me sentí extrañamente consolado, al lidiar con la mecánica cuántica, al aprender la idea del universo dividiéndose en innumerables fragmentos con cada segundo que pasa. A riesgo de sonar ridículo, diría que no elijo conscientemente los temas de mis historias: ellos me eligen a mí. En cuanto a la forma en que se escriben, diría que el contenido lo decide. Sé si la cosa quiere ser novela, poema o lo que sea, aunque a veces la distinción entre memorias y ficción se vuelve un poco borrosa. También estoy de acuerdo con Borges cuando dice que todo lo que escribimos, tal vez todo lo que hacemos, es una ficción.

- Además de escribir, has traducido muchos libros de poesía latinoamericana, por ejemplo una gran antología y más recientemente, Impossible Loves [Amores imposibles] de Darío Jaramillo. ¿Cómo te interesaste en la traducción de poesía latinoamericana y qué relación tiene con tus “propios” textos?

Comencé a traducir del español, en primera instancia, porque pensé, de manera algo inmodesta, que podría hacer un mejor trabajo con Jamie Gil de Biedma que el que se leía en las versiones que inglés que había en ese momento. Y luego, por supuesto, porque la traducción es una adicción, simplemente continué. Traduje lo que me gustó, ya que no necesito hacerlo para vivir (enseño escritura creativa en una universidad, que paga las cuentas). Esta libertad me permitió explorar bastante, y en un viaje a Nicaragua en 2011 conocí a Jorge Fondebrider y Darío Jaramillo, y la idea de una antología de poesía latinoamericana reciente se apoderó de mí y dirigió mi vida, de una manera, por los próximos cuatro años. Me llevó a muchos lugares interesantes y a reuniones con algunas personas notables. La desventaja era que me dejaba cada vez menos tiempo para mi “propia” escritura, ya que todas mis energías parecen canalizarse a ofrecer estas nuevas versiones de los poemas de otras personas. Todavía es difícil encontrar un equilibrio entre los dos: generalmente necesito hacer una cosa u otra, en lugar de intentar ambas. En este momento estoy concentrando en mis propias cosas.

- Tu obra también ha sido traducido al español (El desayuno del vagabundo, tr. Jorge Fondebrider). ¿Ver el espejo desde el otro lado te hace pensar en la traducción de una manera diferente?

Esto es complicado. En muchos sentidos, es más difícil ver la obra de uno mismo traducido a un idioma que uno conoce, y es difícil evitar ser un “pasajero metiche”. Jorge me consultó a fondo enviándome sus traducciones, capítulo por capítulo, pero hubo algunos aspectos—como el uso de argentinismos—con los que me sentía menos cómodo y unos que eran más complejos, como el tono y la textura, que son tan intrínsecos al lenguaje original de un texto que hace que cualquier tarea de este tipo sea casi imposible de lograr con total satisfacción por ambos lados. Al final, solo tienes que dejarlo ir, y creo que Jorge hizo un lindo trabajo. La experiencia me proporcionó ideas, por supuesto, no solo sobre la traducción, sino también sobre el texto original. Creo que la traducción puede ayudarnos a ser mejores escritores, aunque solo sea prestando atención a los pequeños detalles del lenguaje que, de lo contrario, podríamos pasar por alto.

- Durante años has dirigido un blog escrito por un tal ”Ricardo Blanco”. ¿Quién es esta versión alternativa de Richard Gwyn y qué ves como las posibilidades de este espacio para probar ideas, a diferencia de una página impresa?

Ricardo Blanco es una traducción de mi nombre (Gwyn significa “blanco” en galés) y comencé el blog con la idea de filtrar o traducir ideas a través de una versión, o traducción de mí mismo, un tipo de doppelgänger. Las publicaciones durante los primeros años están escritas desde el punto de vista de este alias, por un personaje llamado Blanco, que a menudo se refería a sí mismo en tercera persona, que da a las publicaciones una sensación de desapego doble. Hago menos de eso en estos días, pero la idea sigue presente que esto no es tanto un espacio para la escritura autobiográfica como para las conjeturas de mi alter ego u otro. También escribí la mayoría de las publicaciones del blog de un tirón, sin revisar, para crear una sensación de espontaneidad e inmediatez. No quería un blog pulido, demasiado académico. Eso proporciona un cierto tipo de libertad. Obviamente, escribir lo que sientes en ese momento también puede tener consecuencias desagradables, como cuando la muy eminente escritora nonagenaria Jan Morris respondió a algunas críticas informales de su libro “clásico” sobre Venecia con el comentario: “Lamento que no hayas disfrutado de mi libro. Seguiré intentándolo, de todos modos.” Pero la ventaja de un blog es que puedes regresar y cambiar las cosas post hoc.

- Gran parte de tu obra toma la precariedad como tema, ya sea en términos de finanzas, salud o existencia misma. ¿Cómo entiendes la precariedad en relación con el proceso de escritura y con la vida?

Bueno, es cierto que mi propia vida hasta mediados de la treintena estaba cargada de precariedad, y en base a esa experiencia, adopté muchos de los temas asociados con esa condición en mi escritura: el estado de vagancia, tanto real como metafísico, podría ser una linda metáfora para la vida del escritor. Pero, por otro lado, también podría ser nadar, hacer snorkel o bucear en aguas profundas. O pescar. O soñar.

- ¿Quiénes son los escritores contemporáneos, de cualquier parte del mundo, importantes para ti en este momento y qué es lo que te intriga de su obra?

Esto es difícil, porque cambia todos los meses y son las cosas más recientes que me vienen a la mente. Los poetas que he estado leyendo recientemente y volveré a leer son Adam Zagajewski y Laura Kasischke. Entre los escritores de ficción, soy un gran admirador de Javier Marías y de la próxima generación, Juan Gabriel Vásquez y Andrés Neuman. Lydia Davis, Sarah Manguso y Teju Cole en los Estados Unidos y entre los novelistas británicos contemporáneos más jóvenes, Samantha Harvey y Tom Bullough. En no ficción acabo de leer El vértigo horizontal de Juan Villoro, que es asombroso. También admiro a Geoff Dyer y Rebecca Solnit. This Little Art [Este pequeño arte] de Kate Briggs es uno de mis libros recientes favoritos.

- ¿Qué verso o frase llevas como un amuleto?

“Narrar los eventos como si realmente no los entendieras.” Es Borges, por supuesto, aunque no puedo recordar de dónde. La belleza de este es que es cierto, te guste o no.

- ¿Qué viene a tu mente cuando piensas en la poesía chilena?

¿Para ser honesto? Pienso en el comentario provocador de Roberto Bolaño sobre el tema: “Tengo la vaga sospecha de que para los chilenos la poesía chilena es un perro o las diversas figuras del perro: a veces un manada salvaje de lobos, a veces un aullido solitario oído entre do sueños, a veces, sobre todo últimamente, un perro faldero en la peluquería de perros” (de su ensayo “La poesía chilena y la intemperie”, en Entre paréntesis).

¿Qué quiso decir? Después de todo, él mismo era un poeta chileno. Seguía la discusión entre Bolaño y Raúl Zurita, que continuó mucho después de la muerte de Bolaño. Hasta la ultratumba, si quieres. Fue muy divertido. Siguió pudriéndose hasta la muerte de este último en 2003, e incluso más allá, cuando Zurita dio una entrevista a Chiara Bolognese para los Anales de Literatura Chilena en 2010, en la que afirma que le hubiera gustado haberlo “enfrentado”—utilizando la analogía de una pelea en el patio de la escuela—con el Bolaño “hepático”, uno que Zurita, como él mismo reconoce (ya padecía la enfermedad de Parkinson), probablemente habría perdido, considerando que Bolaño era un luchador en su día, y su padre era un boxeador aficionado. Puedo imaginar la escena lúgubremente cómica: “En la esquina azul, el poeta con Parkinson; en la roja, el novelista con el hígado protuberante.” La idea de esta disputa literaria disolviéndose en una grotesca pelea a puñetazos entre dos inválidos literarios de mediana edad es una que me hace temblar de risa.

Traduje alrededor de veinte poetas chilenos contemporáneos para El otro tigre, creo que más que cualquier otro país representado en la antología, y la selección de quién incluir se hizo increíblemente difícil por la gran cantidad de poetas talentosos en ese país, a través de las generaciones. Sería injusto dar nombres, ya que la selección habla por sí misma.

Mi poeta chileno favorito, quizás pasado de moda, es Jorge Teillier. Creo que algunos de sus poemas se encuentran entre las cosas más bellas y melancólicas escritas por cualquiera en el siglo XX.

- ¿Cómo ha sido tu relación con la obra nerudiana?

Complicado, en una palabra. Me encantaba su poesía cuando era más joven, pero después de reseñar su biografía para una revista hace unos quince años y hacer mi investigación, descubrí tanto que no me gustaba el hombre que no podía evitar de afectar mi lectura del poeta. Sé que no es justo—la historia ha producido escritores con peores CV. Y cuando todo está dicho y hecho, Residencia en la tierra sigue siendo, para mí, una de las obras maestras indiscutibles del siglo XX.

*

“I like ideas that press at the edges of comprehension…”

Interview with Richard Gwyn

–Jessica Sequeira

- Where do you find yourself during the quarantine? What are the books, albums and works of art most important to you in these days of isolation, if there are any?

I don’t mind the lockdown at all. For a writer it seems a very natural way to spend the days, although I do miss my long walks in the hills, which I enjoy not only for their own sake but also as part of the composting process, solvitur ambulando (it is solved by walking) being one of the few Latin phrase I can remember, and which seems truer with each passing year. I might end up just walking, like that Walser fellow, or the character in Thomas Bernhard’s Frost, who embarks on endless ‘expeditions into the jungle of solitude.’ Actually, during lockdown, I’ve dreamed a lot about walking, but it won’t help me lose the kilos I’ve been piling on. I’m currently writing a nonfiction book about my travels across Latin America during 2011-2015 while compiling the anthology The Other Tiger, so my reading is largely dictated by that — or would be, if ever I could follow my own rules. In actual fact most the books I’ve enjoyed reading during lockdown have been connected to pieces I’ve been asked to write: Samantha Harvey’s study of insomnia, The Shapeless Unease and Marina Benjamin’s book on the same topic, titled simply Insomnia, for an essay on, guess what, insomnia. I liked Harvey’s book so much I also read her novel, The Western Wind. I re-read Blindness by Saramago and Love in the Time of Cholera by García Márquez, and ended up writing an essay on the very contemporary notion of contagion. I’ve just finished reading Maya Jasanoff’s The Dawn Watch, a brilliant biography of Joseph Conrad, which examines the way his writing pre-empted globalisation. I’ve been listening to a lot of abstract drone music by people such as William Basinski and Sarah Davachi, while I work at the computer, an acquired taste, I know . . . Art, as in galleries, has not featured as I haven’t been going out, but there has been a constant televisual reminder of how shit everything has been in the UK and how our government messed up badly on COVID. Depressing stuff.

- What books were most important to you in your formation as a writer?

I seem to answer this one differently every time. As a child in a Welsh household, my father played the Richard Burton recording of Under Milk Wood, so that was a background influence for years. Sticking with works of fiction, I was hugely persuaded by One Hundred Years of Solitude, when I first read it in my late teens, but would not want to re-read it now, as I suspect I’d be disappointed. I loved De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium Eater. The Magic Mountain was a revelation, but so too, in its way was V., by Thomas Pynchon, and Les Grands Chemins, by Jean Giono, who remains one of my favourite novelists. I loved The Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys. I was once asked by The Independent newspaper to do their ‘book of a lifetime’ column, and I chose Borges’ Ficciones. I probably still would. I return to Montaigne’s Essays again and again.

- Your novels, like The Colour of a Dog Running Away and The Vagabond’s Breakfast, and your books of poetry, like Stowaway, tend to feature solitary characters who flee from something or seek to remake their life. Often they are found in other countries and languages, caught up in complicated relationships and improbable events, struggling between keeping control and letting themselves go. How do you choose the topics of your books and their style (novel, poetry, etc.)? Or is it a more organic process?

Everything I have ever written is based, to a greater or lesser degree, in my own experience. In reading Borges, I was seduced by the idea that every instant contains the potential for an infinity of outcomes, a recurring motif in his work, or that our universe is only one in a multiplicity of possible universes—an idea that I took up in my novel The Blue Tent—or that rather than being the proprietors of our own consciousness, we are being dreamed by some other entity. I like ideas that press at the edges of comprehension, and have always been dissatisfied with received wisdoms. The idea of multiple lives—and of multiple worlds—is one that has been with me as long as I can remember. I was strangely comforted, when grappling with quantum mechanics, to learn the idea of the universe splitting into innumerable fragments with each passing second. At the risk of sounding ridiculous, I’d say that I don’t consciously choose the themes of my stories: they choose me. As to the form they get written in, I’d say the content decides that. I know whether the thing wants to be a novel, or a poem, or whatever, though sometimes the distinction between memoir and fiction becomes a little blurred. I’d also go along with Borges when he says that everything we write, perhaps everything we do, is a fiction.

- In addition to writing, you have translated many books of Latin American poetry, including a big anthology and more recently, Impossible Loves by Darío Jaramillo. How did you grow interested in translating Latin American poetry and what is its relationship to your ‘own’ work?

I started translating from Spanish, in the first instance, because I thought, rather immodestly, that I could do a better job on Jaime Gil de Biedma than the English versions that were on offer at the time. And then, of course, because translation is an addiction, I just carried on. I translated what I liked, as I do not need to do it for a living (I teach creative writing at a university, which pays the bills). This freedom allowed me to explore quite widely, and on a trip to Nicaragua in 2011 I met Jorge Fondebrider and Darío Jaramillo, and the idea of an anthology of recent Latin American poetry took hold of me, and steered my life, after a fashion, for the next four years. It took me to many interesting places, and meetings with some remarkable people. The downside was that it left me less and less time for my ‘own’ writing, as all my energies seems to be channeled into providing these new versions of other people’s poems. It’s still difficult to find a balance between the two: I generally need to be doing one thing or the other, rather than attempting both. Currently I’m focusing on my own stuff.

- Your work has also been translated into Spanish (El desayuno del vagabundo, tr. Jorge Fondebrider). Does seeing the mirror from the other side make you think of translation in a different way?

This is difficult. In many ways it’s harder to see one’s work translated into a language one knows, and it’s difficult to avoid being a ‘back seat driver.’ Jorge consulted with me quite thoroughly by sending me his translations, chapter by chapter, but there were some areas—like the use of Argentinisms—that I was less comfortable about, and more complex ones such as tone and texture that are so intrinsic to the original language of a piece that it makes any task of this kind almost impossible to achieve with complete satisfaction on both sides. In the end, you just have to let it go, and I think Jorge did a good job. The experience did provide me with insights, of course, not only about translation, but about the original text. I do think that translation can help us to become better writers, if only by paying attention to the small details of language that otherwise we might let pass by.

- For years you have run a blog written by ‘Ricardo Blanco’. Who is this alternate version of Richard Gwyn and what possibilities do you think this space offers to try out ideas, as opposed to the printed page?

Ricardo Blanco is a translation of my name (Gwyn means ‘white’ in Welsh) and I started the blog with the idea of filtering or translating ideas through a version, or translation of myself, a doppelgänger of sorts. The posts during the first few years are written from the point of view of this alias, by a character called Blanco, who often referred to himself in the third person, lending the posts a sense of detachment twice over. I do less of that these days, but the idea is still there that it is not so much a space for autobiographical writing, as the conjectures of my alias or other. I also wrote most of the blog posts in one sitting, without revision, in order to create a sense of spontaneity and immediacy. I didn’t want a polished, overly academic kind of blog. That provides a certain kind of freedom. Obviously, writing what you feel at the time can also have unwelcome consequences, such as when the very eminent nonagenarian writer Jan Morris responded to some offhand criticism of her ‘classic’ book on Venice with the comment ‘So sorry you didn’t enjoy my book. I’ll keep trying, anyway.’ But the advantage of a blog is that you can go back and change things post hoc.

- A large part of your work takes precarity as its theme, whether in terms of finances, health or existence itself. How do you understand precarity in relation to the process of writing and to life?

Well, it’s true my own life up until my mid-thirties was fraught with precarity, and based on that experience, I adopted many of the themes associated with that condition in my writing: the state of vagrancy, both actual and metaphysical, might be a nice metaphor for the life of the writer. But then again, so might be swimming, or snorkeling or deep-sea diving. Or fishing. Or dreaming.

- Who are some contemporary writers, from any part of the world, important to you at this moment and what is it that intrigues you about their work?

This is hard, because it shifts every month, and it’s the most recent things that come to mind. Poets I’ve recently been reading, and will return to, are Adam Zagajewski and Laura Kasischke. Among fiction writers I am a big fan of Javier Marías, and of the next generation down, Juan Gabriel Vásquez and Andrés Neuman. Lydia Davis, Sarah Manguso and Teju Cole in the USA and among younger, contemporary British novelists, Samantha Harvey and Tom Bullough. In nonfiction I’ve just been reading Juan Villoro’s El Vertigo Horizontal, which is astonishing. I also admire Geoff Dyer and Rebecca Solnit. Kate Briggs’s This Little Art is one of my favourite recent books.

- What verse or phrase do you carry as an amulet?

‘Narrate events as though you don’t really understand them.’ It’s Borges, of course, though I can’t remember from where. The beauty of this one is that it’s true whether you like it or not.

- What comes to your mind when you think of Chilean poetry?

Honestly? I think of Roberto Bolaño’s provocative remark on the subject: ‘I have a vague suspicion that Chileans see Chilean poetry as a dog, or as dogs in their various incarnations: sometimes as a savage pack of wolves, sometimes as a solitary howl heard between dreams, and sometimes—especially—as a lap dog at the groomers.’

What did he mean? After all, he was a Chilean poet himself. I followed the argument between Bolaño and Raúl Zurita, which continued long after Bolaño’s death. Into the afterlife, if you like. It was hilarious. It festered on until the latter’s death in 2003, and even beyond, Zurita giving an interview with Chiara Bolognese for the Anales de Literatura Chilena in 2010, in which he claims he would have liked to have ‘had it out’—using the analogy of a schoolyard brawl—with the ‘hepatic’ Bolaño, one which Zurita, as he himself concedes (he was by now suffering from Parkinson’s disease), would probably have lost, considering Bolaño was something of a brawler in his day, and his father was an amateur boxer. I can picture the bleakly comic scene: ‘In the blue corner, the poet with Parkinsons; in the red, the novelist with the knobbly liver.’ The idea of this literary tussle dissolving into a grotesque fistfight between two middle-aged literary invalids is one that makes me shake with laughter.

I translated around twenty contemporary Chilean poets for The Other Tiger—more than any other country represented in the anthology, I believe—and the selection of who to include was made incredibly difficult by the sheer number of talented poets in that country, across the generations. It would be invidious to name names, since the selection speaks for itself.

My favourite Chilean poet, perhaps unfashionably, is Jorge Teillier. I find certain of his poems among the most beautiful and melancholy things written by anyone in the twentieth century.

- What has your relationship been with the work of Neruda?

Complicated, in a word. I loved his poetry when I was younger, but after reviewing his biography for a magazine some fifteen years ago, and doing my research, I discovered so much I disliked about the man that it couldn’t help but affect my reading of the poet. I know that isn’t fair — history has produced writers with worse CV’s. And when all is said and done, Residencia en la tierra [Residence on Earth] remains, for me, one of the indisputable masterpieces of the twentieth century.